Greg Wyler is a prominent figure in the world of telecom. Elected the industry’s most powerful personality in 2017, the 50-year-old American engineer and business leader is famous for combining innovation, business success and social responsibility to bridge the digital divide on a global scale.

Greg Wyler is a prominent figure in the world of telecom. Elected the industry’s most powerful personality in 2017, the 50-year-old American engineer and business leader is famous for combining innovation, business success and social responsibility to bridge the digital divide on a global scale.

After working in Rwanda with a plan to bring broadband to the African nation’s schools, Greg Wyler launched the company O3b Networks in 2007. Its objective: to create a constellation of innovative satellites capable of bringing broadband internet to poor countries deprived of fibre optics. He also set up Oneweb, which has also launched a constellation designed to “bring internet to everyone”.

The two businesses, which Wyler left following their resales in 2016 and 2020, raised more than four billion euros from investors as renowned as Google, Liberty Global, Qualcomm and HSBC.

The American contractor is also a major customer of the French space industry: O3b Networks bought its satellites from aerospace giant Thales, launched them through Arianespace in Kourou, French Guiana, and obtained a $465 million guarantee from Coface, the French public export credit agency.

Greg Wyler’s second company, OneWeb, has been a pioneer in the race for a galactic internet, and has been challenged by competing projects from Elon Musk’s SpaceX. OneWeb has raised $3 billion to create a new type of constellation of 640 low orbit microsatellites, capable of offering broadband internet worldwide.

Oneweb has chosen Airbus as its main industrial partner. The deal has been labeled “the contract of the century” in the press and was announced in presence of French president François Hollande and Airbus CEO Thomas Enders at the Paris Air Show in June 2015. OneWeb filed for bankruptcy in March 2020 after having launched only 60 satellites.

But Greg Wyler’s success story has a dark side. For at least seven years, Greg Wyler has conducted several suspicious transactions through offshore entities based in tax havens. This is revealed by the Jersey Offshore documents investigated by Nacional and Mediapart and its partners in the EIC network.

The 350,000 pages of documents are from the archives of La Hougue, a Jersey-based offshore service provider. Our previous investigation demonstrated the firm’s methods of facilitating the tax evasion of some of its clients, including the fabrication of false documents to launder money transfers in tax havens.

The documents we obtained indicate that La Hougue managed a secret trust in Jersey for Greg Wyler, whose assets were used to grant a strange circular loan, buy a flat in London and a Cartier watch.

Our documents also show that Greg Wyler and the founder of La Hougue set up a secret business in the British Virgin Islands that allowed them to siphon funds from the Rwanda-based telecom operator Rwandatel.

Wyler’s lawyer, Julie de Lassus Saint-Geniès, replied that her client believes that our documents “are at best unreliable and at worst falsified and fraudulent”, which we dispute.

Wyler denies having been a client of La Hougue, to whom he “did not ask” to “manage anything for him”. He says he “invested” in only one company created by La Hougue in the British Virgin Islands, which had operations in Rwanda. Then he sold his shares and declared all this income to the U.S. tax authorities.

“Any suggestion on your part that Mr. Wyler has engaged in tax evasion would not only be erroneous, it would be completely insulting,” writes his lawyer, adding that “Greg Wyler has no knowledge of La Hougue’s activities […], past or present.”

The trust in Jersey and the Cartier watch

For twenty years, Greg Wyler has been a friend of John Dick, the 82-year-old Canadian millionaire, who made his fortune as a real estate developer in the United States and then founded the financial services company La Hougue in Jersey, which he controlled in secret for over thirty years.

It all started in the early 1990s, when Wyler was a student and already an entrepreneur: he had his first success by setting up a computer components company, which he sold after his studies.

The young man is taking summer courses at a Suffolk Law School in Boston. There he meets a classmate, Tanya Dick, John’s daughter. Thanks to Tanya’s insistence, they meet each other. Wyler makes a strong initial impression on Dick, and the Canadian millionaire becomes the young American’s mentor. “I can certainly say that if I had not met John or had his influence or mentorship, there would not have been an O3b,” Greg Wyler told Via Satellite website.

Dick also seems to have convinced his protégé to work with La Hougue. Greg Wyler appears in La Hougue’s confidential client list, under code C0326, as a beneficiary of the Nile River Trust, a Jersey-based trust, a structure reputed for its opacity in the small world of tax havens.

Greg Wyler tells us that he does not know anything about the Nile River Trust, which he has “never heard of.”

Numerous internal documents, including memorandums and bank statements, however, link this trust to Greg Wyler, and to several transactions in which he was actually involved.

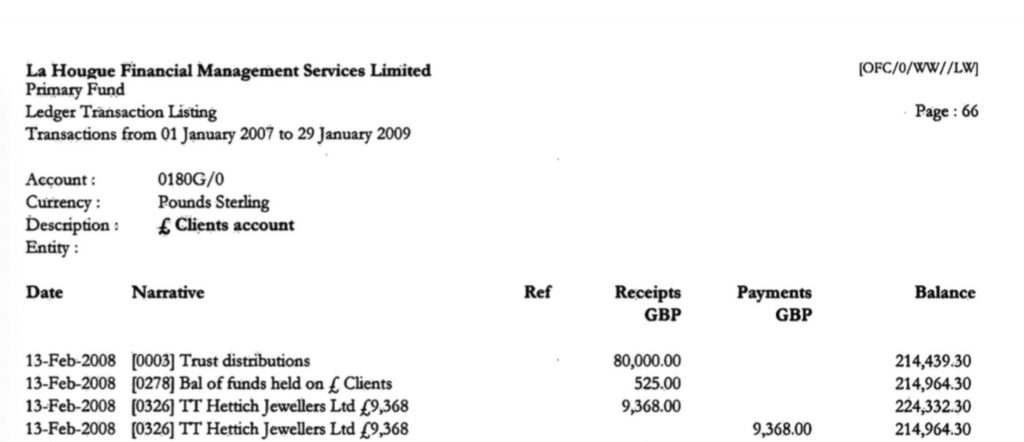

On 6 February, 2008, the American entrepreneur writes to James Wigley, an employee of La Hougue and son of the general manager. He wants to buy a Cartier watch model Tortue from a jeweller in Jersey. Wigley contacts immediately the jeweller’s to ask them to give Wyler the 15% discount that John Dick enjoyed. One week later, La Hougue buys the watch for £10,943, debiting the account C0326. That of the Nile River Trust.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.nacional.hr/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/1-Correspondence-with-jeweller-to-receive-discount-for-Wylers-Cartier-watch-6-February-2008.pdf” title=”1 Correspondence with jeweller to receive discount for Wyler’s Cartier watch – 6 February 2008″]

A suspicious circular loan

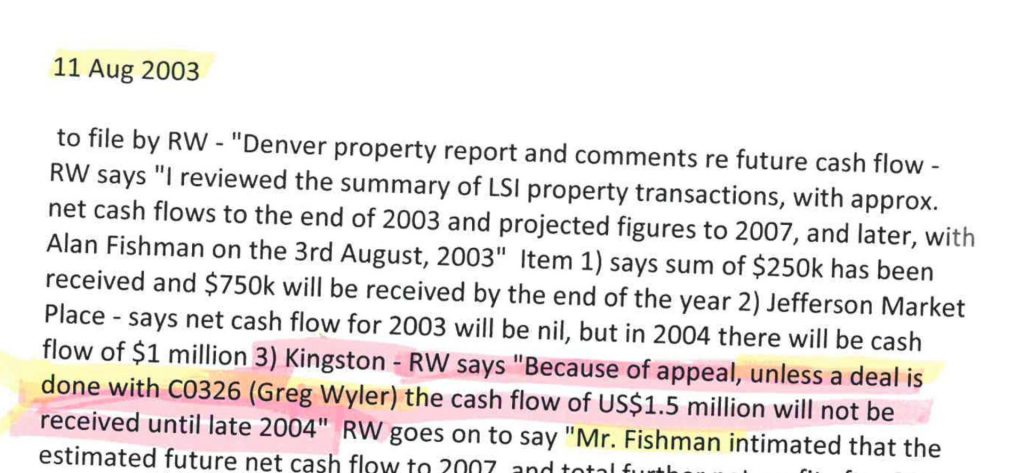

The Nile River Trust appears in the archives of La Hougue from 2003. At that time, John Dick needs money to finance a real estate company in the United States, and wants to convince Greg Wyler to invest through his trust. “Unless an agreement is made with C0326 (Greg Wyler),” a file note from August 2003 states, “cash will be short.” The American entrepreneur seems to have refused at first.

In the same year, 2003, Greg Wyler lends $500,000 to La Hougue. According to file notes and bank documents, the money comes from “C0326”, the Nile River Trust, and the loan was negotiated personally by John Dick.

The operation is unusual to say the least. With Wyler’s money, La Hougue makes a loan to the offshore company Quartz International Finance, at an interest rate of 7.5%. Quartz immediately loans the $500,000 to Oxford Financial Services at a rate of 8.25%. And Oxford loans the money back to… La Hougue, thus completing a circular loan.

According to Tanya Dick-Stock, this operation is one of the fake loans organised by her father to divert to his benefit the trust money belonging to his two children. He will be judged next year for these accusations, which he contests.

Tanya Dick-Stock claims that John Dick pocketed the principal, while the interest difference (eventually reduced to 8% a year later) was used to pay La Hougue employees. This is even though the repayment and interest were made by trusts owned by Tanya and her brother.

Internal documents show that Greg Wyler was reimbursed by John Dick in December 2010 and April 2011, but with funds from the auction of luxury cars owned by one of his children’s trusts.

John Dick refused to answer journalists’ questions on this issue. And nothing in the documents suggests that Greg Wyler knew what La Hougue was doing with his money.

In any case, the loan proved to be very lucrative for Wyler, since he received about $40,000 in annual interest over eight years. The money was credited to the Nile River Trust account in Jersey.

“Mr. Wyler knows nothing about the alleged loans,” his lawyer told us.

The London flat and the shell company

Since 2004 Greg Wyler has been involved in a real estate project. He personally negotiated the purchase of a flat in London, which became his temporary residence in Europe. He orchestrated the renovation of this comfortable 113 m2 flat in the high-class Kensington district.

Payment of invoices is carried out by La Hougue in Jersey. In his numerous exchanges of e-mails with the firm on this subject, Greg Wyler insists that he must not appear.

“I didn’t mention the name Wyler,” he writes to James Wigley, his contact at La Hougue, about an electricity bill. “Can you please send a fax to London Electric that the flat should be in the name of Lisson Holdings and then set up for the billing to go direct to Lisson Holdings,” he says in another email. In a third, Greg Wyler asks James Wigley to transfer some bills to Lisson Holdings, because they are at that time “in [his] name” and “really need to be transferred”.

The flat was acquired by Lisson Holdings, a company registered in the British Virgin Islands, one of the world’s most notorious worst tax havens. The directors are officially employees of La Hougue, who serve as nominees. But several internal documents show that Lisson paid for the flat and its renovation with funds from the Nile River trust, which lent it a total of £940,000.

In order to muddy the waters a little more, this loan was accounted for by La Hougue as being granted by The Russian Trust, which belongs to the children of John Dick. But in reality, the £940,000 is entirely “from 326 [the Nile River Trust’s code],” James Wigley told a colleague, who was obviously confused.

In 2011, Greg Wyler then acquired the flat from Lisson Holdings, and therefore appears to have bought it back from himself. It looks like one of the eleven techniques described in an internal memo from La Hougue for transferring offshore assets.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.nacional.hr/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/4-James-Wigleys-note-explaining-background-of-London-flat-purchase-16-August-2011.pdf” title=”4 James Wigley’s note – explaining background of London flat purchase – 16 August 2011″]

Greg Wyler denies to EIC Network this and says that prior to 2011 the flat was owned by John Dick. “Mr Wyler agreed to find and remodel a flat in London for Mr Dick, [and] was to potentially receive some of the profit from the sale of the flat, while still being able to stay there,” says his lawyer.

Except that this version is described in an internal document of 2011 as the official explanation to be provided in order to hide the reality.

In this file note, James Wigley explains that John Dick asked him in 2004, following an agreement with Greg Wyler, to “set up a corporation for GW, if I had not done so already, which would purchase the property. All monies would appear at first glance that the Russian Trust provided monies into corporation. John Dick said that he was going to represent this and say that he was allowing GW and his family to stay there on an occupation basis.”

The memo states that “John Dick was more than happy to do this” given the significant “returns” he has achieved thanks to Greg Wyler “in Rwanda”.

Rwanda’s offshore profits

Nothing in their past could suggest that the two men would end up doing business in this poor African country, ravaged by the 1994 genocide. They told the Via Satellite website that it all began in the early 2000s with a visit by Greg Wyler to Rwanda, where he met the country’s President Paul Kagame. Wyler told the head of state that his friend John Dick, a real estate expert, could help him with the urban plan for the capital Kigali.

A few weeks later, President Kagame spends 48 hours in the UK for talks with Prime Minister Tony Blair. He extends his trip by two days to visit Dick and Wyler on the island of Jersey. He then invites the two men to visit Rwanda in VIP mode, with travel by military helicopter.

John Dick becomes close to Kagame, and quickly takes advantage of this relationship. In June 2003, he is appointed Honorary Consul of Rwanda in Jersey, then “ambassador at large” of the country, to the point of obtaining a diplomatic passport in 2011. In 2017, President Kagame personally decorates him with Rwanda’s highest honour for “exemplary service to the nation”.

La Hougue’s internal documents suggest that John Dick used his good relations with President Kagame as an intermediary. A memorandum states that John Dick helped a Russian businessman to “develop mining opportunities” in Rwanda, for which he is to “receive 5% [of the project] free of charge”.

John Dick “has not received any remuneration for his role [in Rwanda] and has not abused his relationship with the president,” his lawyers told EIC Network.

Dick and Wyler’s African adventure began with the Terracom company in 2003. The objective: to connect Rwandan schools to the internet, building the country’s first fibre optic and wireless networks. With the support of the Rwanda government, which paid $1.5 million to Terracom in 2004.

Rising technology star Greg Wyler’s commitment to such a poor country has attracted the attention of the press, from the New York Times to the Wall Street Journal. However, the young man is struggling on the ground to build his network from scratch in difficult conditions. He has transported tons of material to an altitude of 4,500 metres above sea level to renovate an old radio antenna, installed at the top of a volcano, Karisimbi.

“I had gone to the country purely just to see if there’s a way I could help,” said Wyler about that time. “We never went to Rwanda to make money, but it wasn’t pure charity either,” his partner John Dick said.

Some aspects of the business were indeed not very charitable. The Rwandan company Terracom belonged to Far East Trading Developments, an offshore shell company managed by La Hougue and registered in the British Virgin Islands, where taxation is zero. According to a file note, the two partners had an agreement to share the investments and then the profits for all their activities in Rwanda: 71% for Wyler and 29% for Dick.

Terracom has not been a great success for schoolchildren in the country. A report by Rwanda’s Auditor General, the equivalent of our State Audit Office, concluded in 2010 that Terracom had committed to connecting 300 schools by December 2006, but that only 85 were connected two years later. Greg Wyler says it was because of problems for which he was not responsible, such as a lack of electricity and computers.

In 2005, the business of the two partners changed dimensions when President Kagame asked them to take control of the public telecommunications operator Rwandatel. The contract stipulates that Terracom bought Rwandatel for $20 million, of which only $5 million was payable immediately, with the balance spread over 10 years.

Dick and Wyler found a trick to channel part of Rwandatel’s cash flow into tax havens for their own benefit. In 2004, they set up Global Market Traders Group (GMTG) in the British Virgin Islands (BVI). It buys bandwidth from major satellite telecom operators and then sells it to Terracom and Rwandatel. According to an internal memo from La Hougue, Wyler “masterminded” this activity.

Bank documents show that it was highly lucrative: In 2005, GMTG bought $418,000 worth of bandwidth, which it sold for more than twice that amount to Rwandatel, for $977,000. In the same year, GMTG transferred $436,000 in profits to La Hougue in Jersey.

Greg Wyler “has no recollection of this activity,” his lawyer told us.

In October 2005, Greg Wyler wants to launch a second intermediary business, this time to buy telecom equipment and resell it to Rwandatel.

He writes to James Wigley, his contact at La Hougue, to ask him to set up UTStarcom Africa, which he needed in order to “split the purchases”. The company must be incorporated “in the BVI or off Jersey location,” he says. “I expect some initial payments as soon as the banking is set up.”

But with Rwanda classified as a “high-risk” country, the bank wants to know the “name of ultimate beneficial owner” of the company, writes James Wigley to Wyler. To avoid this, he proposes to open the bank account under the name of La Hougue. “I am not sure we need to have the UTStarcom Africa company anymore, as we may be going with [Chinese equipment manufacturer] ZTE,” Wyler replies.

The two partners’ investment in Rwanda was quickly derailed. In 2006, the relationship with President Kagame cooled down after Greg Wyler tried to bring a Rwandan-born South African billionaire, Miko Rwayitare, into the deal.

This initiative was discussed in December 2006 during a meeting at the La Hougue headquarters in Jersey, with the boss John W. Dick.

“The business relationship with Miko will cause problems with the Govemment as they feel that many promises that were made have not been fulfilled,” the minutes say.

At the same meeting, Dick says he was concerned “at the way GW is handling some areas of the business, [which] is likely to be increasing scrutiny of the companies activities including the auditing of accounts.” John Dick “feels he has been kept out of the loop with a lot of GW’s dealings and is nervous of his actions and motives. He mentioned that GW is making poor decisions as well as purely looking after himself with this arrangement.”

The draft agreement with Rwayitare was finally cancelled. And the government decided to buy out Terracom and its subsidiary Rwandatel in 2007. After difficult negotiations, Rwanda agreed to pay $11.9 million. The two partners, who had been paid $5 million two years earlier, therefore took almost $7 million in raw profit from Rwanda and through the British Virgin Islands. Greg Wyler says this figure is “inaccurate”.

Former La Hougue Executive Chairman Richard Wigley and his son James referred to the transaction in a 2017 court deposition: “We are unable to comment as to the actions of Mr. John Dick Snr. and his partner, Greg Wyler, but we understand they were concerned for tax reasons not to receive proceeds from the sale of Rwanda assets in their own names.”

When the money comes back to the United States

Greg Wyler vigorously denies this. He points out that Richard Wigley’s reliability is “doubtful”, given that he has falsified documents. Wigley did admit to having done so, but some of the forged documents were intended to help La Hougue’s clients hide their money.

The American entrepreneur says he invested in Far East Trading Developments, the company in the British Virgin Islands that owned the Rwandan operations, then sold its shares in 2007 and 2008 and reported all of its income in the United States. Greg Wyler acted “in full compliance with tax requirements and was in no way seeking to reduce his U.S. taxes,” writes his lawyer.

This sale of shares is surprising, given the more than demonic profile of the company in which Wyler says he “invested”. Numerous documents show that Far East Trading Developments was, for at least thirty years, one of the main offshore shell companies used by La Hougue in its tax evasion schemes.

Far East Trading Developments was a “taxi company”, which served to make transactions more opaque and to allow customers to discreetly transfer their money to Jersey. In 1998, La Hougue offered to its clients to write cheques to Far East Trading Developments, with this advice: “If ever asked, you purchased something in the Far East, and we can always back up should the need arise”. By means of fake invoices, which were sometimes provided to customers.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.nacional.hr/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/6-Wyler-changing-flat-costs-invoices-to-Lisson-Holdings-3-October-2005.pdf” title=”6 Wyler changing flat costs invoices to Lisson Holdings – 3 October 2005″]

In short, it is strange that Greg Wyler was a shareholder in such a company. “I assume that the shareholding of […] Far East is not available”, he wrote in 2007 to employees of La Hougue, when he sold Far East Trading’s subsidiary Terracom to the government of Rwanda.

Our documents draw another possible explanation. On 14 November, 2007, Richard Wigley writes to a colleague at La Hougue that a client wants to “repatriate the majority of his monies early next year”, a move he considers extremely “unusual”: “I asked him to consider his position that, once the monies had been returned, the act would be irreversible”. The rest of the email describes the assets listed by La Hougue as belonging to Greg Wyler, including the Nile River Trust and the company that owns the London flat.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.nacional.hr/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/5-Deposit-for-London-flat-paid-by-C0326-or-Nile-River-Trust-10-August-2004.pdf” title=”5 Deposit for London flat paid by C0326 or Nile River Trust – 10 August 2004″]

On 21 December, 2007, the Nile River trust made a transfer (“funds out”) of $1.1 million, and a second of $3 million in May 2008, which is consistent with the payments reported to the tax authorities by Wyler. A month later, the Nile River Trust transferred an additional $3.5 million to the account of Pantrust, the new name La Hougue took on when the firm moved to Panama in 2007.

Was the sale of Far East Trading Developments shares a cover to justify sending money back to the United States? Greg Wyler denies this, but refused to comment on the documents we submitted to him on this subject. He adds that he “never invested in any company in Panama”.

Richard and James Wigley, through their lawyer, refused to comment, saying our questions are based on “blatantly false” facts. President Paul Kagame, contacted through the Government of Rwanda’s press office, did not respond to questions.

Jersey’s satellites

Just after the sale of Rwandatel, Greg Wyler launched his first space-based telecommunications company in late 2007, inspired by the lack of satellite bandwidth he suffered in Rwanda. The goal of O3b Networks, which stands for “the other 3 billion” people without internet, is to launch a constellation of a new kind of satellites, capable of efficiently connecting poor countries, particularly in Africa.

Wyler has chosen to register O3b Networks in Jersey, where corporate tax is zero. The confidential business plan dated 2008 indicates that O3b Networks will only own the satellites and will employ 20 people on the island, while most of the activity will be carried out by its American subsidiary. Greg Wyler says that he did not set up O3b Networks Jersey’s headquarters for tax reasons.

He once again called on La Hougue to create the company and take care of its administrative management. He also convinced his friend John Dick to invest in it. Dick was appointed as Chairman of the Board of Directors of O3b, where La Hougue’s CEO Richard Wigley also sits. The head office was set up at the St. John‘s Manor, John Dick’s home and La Hougue’s headquarters until its move to Panama.

In a note written on 23 November, 2007, La Hougue CEO Richard Wigley says that John W. Dick and Greg Wyler began discussing a possible arrangement regarding O3b Networks: “[JWD] indicated that Greg had suggested that JWD be seen to have 11% of the company, part of which would be due to Greg or his assigns. The “part” has yet to be agreed and there may be some arrangement whereby JWD holds whatever the percentage is due back to Greg in trust for his daughters or it is gifted in due course.”

“Neither Mr. Greg Wyler nor any member of his family were the beneficiaries” of O3b Networks shares held by third parties, says his lawyer.

After raising $1.2 billion from investors such as Google, HSBC Bank and US cable television giant Liberty Global (of which John Dick is a director), O3b Networks was acquired in 2016 by Luxembourg’s SES, one of the world’s largest satellite operators.

In 2012, Wyler launched a second company, OneWeb, based on the same model as O3b, but with new low-orbit satellites manufactured in partnership with Airbus. The entrepreneur chose, once again, to register OneWeb in Jersey. But this time there is no link with La Hougue and John Dick.

Despite his problems in Rwanda between 2005 and 2007, Greg Wyler managed to maintain good relations with Paul Kagame. In 2017, the Rwandan president supported him on Twitter to win the award for the most powerful telecoms leader of the year.

In 2018, the head of state invited Greg Wyler to attend the Smart Africa Summit in Kigali, while the Rwandan state bought 1.7% in OneWeb. In 2019, in partnership with the Government of Rwanda, OneWeb launched a satellite called Icyerekezo to “bridge the digital divide” for rural Rwandan schools – the same objective Terracom had sixteen years earlier.

OneWeb filed for bankruptcy on 27 March 2020 and was subsequently acquired by a consortium led by the UK government and Indian conglomerate Bharti Global.

The spaceman and the Jersey manor

Greg Wyler says he hasn’t had a business relationship with John Dick in ten years. But the two men have remained close. The founder of La Hougue is now embroiled in a fierce legal battle with his daughter Tanya, who accuses him of embezzling money from trusts set up for her and her brother.

At the beginning of 2019, John Dick had a big worry about St. John‘s Manor, a sumptuous, historic building in Jersey where he has lived for nearly forty years. His daughter was able to prove that John Dick was not the beneficiary of the trust holding the mansion, and put it up for sale. The master of the stately home may have to leave.

In February 2019, his friend Greg Wyler made an offer to buy the manor for £12 million, plus 1,750 OneWeb shares. The deal did not go through in the end.

Greg Wyler admits that he spoke to John Dick about the mansion before making the offer, but formally denies that he wanted to help him. He says he was considering emigrating to Jersey at the time, and settling in the castle “with his family”, before realising that “it wasn’t the right solution for them”.

The satellite champion stayed in the United States. And the founder of La Hougue, lord of St.John‘s Manor and the offshore schemes, left his manor on 21 January 2020.

Komentari